The Cartier Vintage is a special program brought by the Maison featuring rigorously sourced and restored vintage AAA Cartier replica watches from 1970s to 2010s. The program has been available in London and Paris, and now comes to the flagship Cartier boutique in ION Orchard. The first 6 top Canada fake watches have landed, and here is a peek into what is on offer. Drop in the Boutique to view.

Showcasing the Maison’s watchmaking timelessness heritage, luxury replica Cartier Vintage watches, as a collection, pays tribute to the unique Cartier shapes that date from 1970s to 2010s and assures the authenticity of these symbolic creations.

The Cartier Vintage Program

The inception of Cartier Vintage begins at sourcing and is helmed by a group of experts from the Image, Style & Patrimony department as they work with trusted partners from watch fairs to specialised retailers and internal teams to authenticate the selected creations. Upon successful validation, the high quality fake Cartier watches are restored by the Maison’s finest talents in the Manufacture department as they go through a strict restoration policy including quality control to ensure their functionality whilst keeping to their originality.

Following London and Paris, Singapore extends its watchmaking offering with Cartier Vintage as a continual effort to engage with local watchmaking enthusiasts.

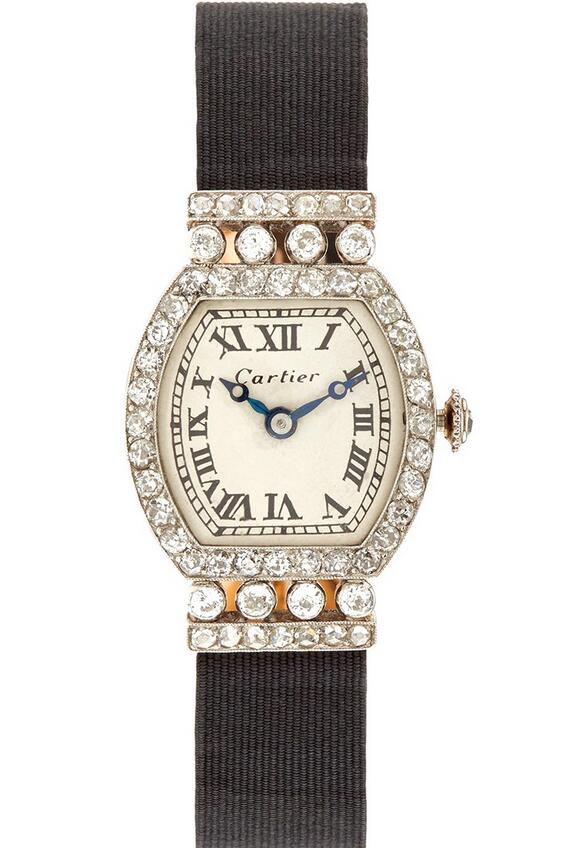

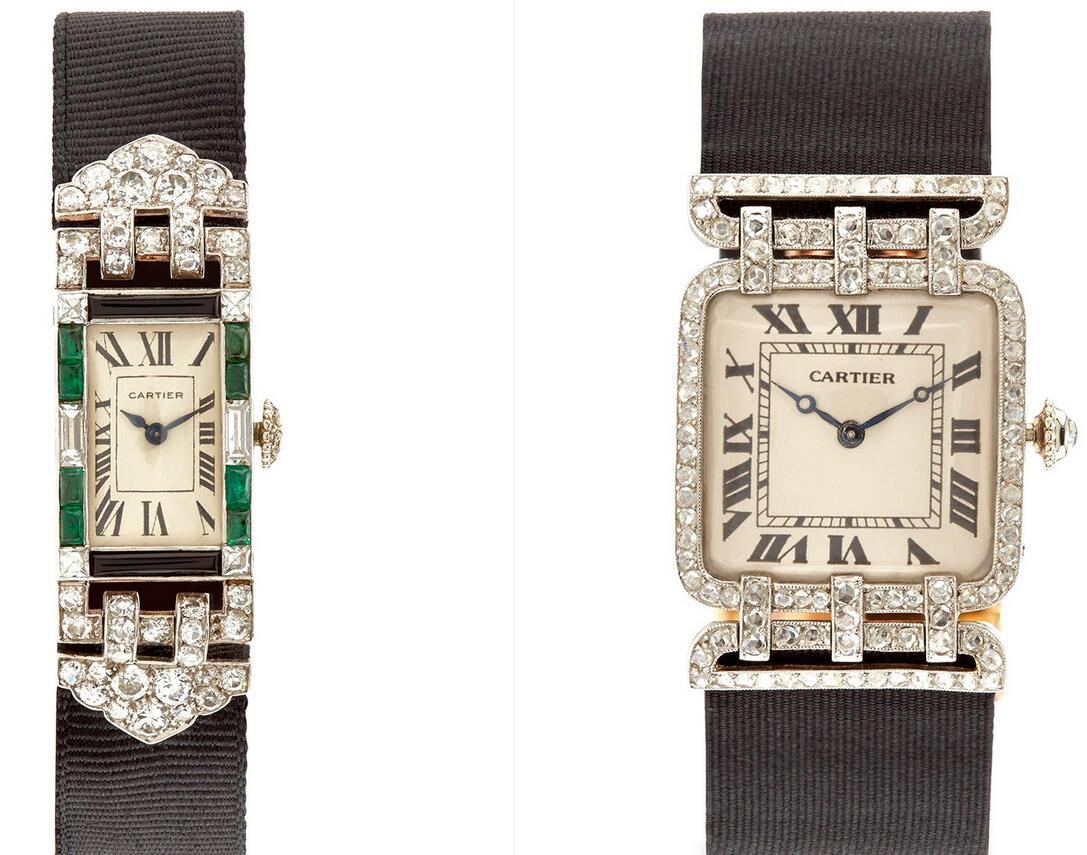

Epitomising the beauty, diversity and timelessness of 1:1 Cartier replica watches’ patrimony, the Cartier Vintage assortment in Singapore has a total of six pieces ranging from Tank, Tonneau to Tortue. For an unparalleled client experience, each purchasing client will receive an 8-year warranty through Cartier Care, new authenticity certification alongside the signature Cartier red box.

Collection currently in Singapore, subject to prior sales

The Cartier Vintage offering in Singapore consists of six perfect copy watches from four different collections.

Collection Louis Cartier: Square Incurvée Square

Between 1981 to the mid-1990s, all solid gold best replica Cartier watches in the Maison were grouped together under “Collection Louis Cartier”, which saw a combination of classic Cartier designs from Tank to Tonneau and original Cartier creations from Cloche to Square Incurvée.

As a complete range of timepieces highlighting the Maison’s devotion to shaped top Cartier fake watches, Collection Louis Cartier was enriched with multiple interpretations over the years including Baignoire, Ceinture and Ellipse with their double or triple gadroon cases as a highlight in the 1980s. As a result, this had distinguished itself from other Cartier watchmaking segments in the likes of Santos de Cartier and Must de Cartier.

Square curved watch, large model, hand-wound mechanical movement, yellow gold, leather (1976)

Movement: ETA 078

Characteristic: Manual winding

Dimensions: 17.5mm by 2.9mm

Power reserve: 38 hours

Frequency: 21,600 alt./hour

Number of jewels: 17

Launched in 1973, the Cristallor and Square Incurvée replica watches for sale continued to pay tribute to the Maison’s exploration in geometry and the art of clean lines. Notable for the solid gold cases with a gadroon decor, other Cartier watchmaking codes were added from Roman numerals to blue cabochon to make these creations look bold in this era.

Atelier de Paris MCHP (Manufacture Cartier Horlogerie Paris): Tonneau

In the beginning of the 1980s, a part of the watchmaking production was moved from Switzerland to Paris, which saw the initiation of Manufacture Cartier Horlogerie Paris. It was existing until the beginning of the 21st century. During this period, many Cartier super clone watches shop creations were made in France and carried distinctive features including precious materials and “Cartier Paris” on a white dial.

Tonneau watch, small model, manufacture mechanical movement with manual winding, yellow gold, leather (1985)

Movement: ETA 078

Characteristic: Manual winding

Dimensions: 17.5mm by 2.9mm

Power reserve: 40 hours

Frequency: 21,600 alt./hour

Number of jewels: 17

The first Tonneau watch was born in 1906, which helped to challenge the tradition of round pocket Cartier replica watches site back in the days. Aimed to fit well on the wrist, the case was designed to curve slightly with the dial shaped in between a rectangle and an oval. The “vis armurier” tube screws adorning the lugs was a strong point of design to further enhance its avant-garde aesthetic in the early 1900s. Paired with a leather strap, its true beauty was underlined with the juxtaposition of precious and natural materials.

Collection Privée Cartier Paris (CPCP): Tank à Vis Dual Time Zone

Initially launched in Switzerland and Italy in 1998 before making it available worldwide in 1999, Collection Privée Cartier Paris was a curated collection of Swiss movements fake Cartier watches for watchmaking connoisseurs. Some of the characteristic codes included the precious case metal from yellow gold to platinum, alligator leather strap with a folding buckle, “Cartier Paris” on a guilloché dial and mechanical movement (with or without complications).

Tank à Vis watch, large model, hand-wound mechanical movement, yellow gold, leather (2002)

Movement: 9901 MC

Characteristic: Manual winding

Dimensions: 26mm by 20.3mm

Power reserve: 38 hours

Frequency: 21,600 alt./hour

Number of jewels: 18

In 1931, Jaeger-LeCoultre and Cartier achieved a major technical innovation of ensuring the water resistance of a rectangular watch case through the Tank Étanche creation. Inspired by Tank Étanche, best quality replica Cartier Tank à Vis watches was launched in 2001 with rounded case sides and bezel studs with screws. The dual time zone complication, a complication seen on Tank Cintrée or Tonneau, was different on Tank à Vis with one movement and a crown to wind the watch and set the times.

Collection Privée Cartier Paris (CPCP): Tortue Minute Repeater

Designed in 1912, the tortoise-inspired case shape was an instant hit with watch lovers and fitted right into the Maison’s collection of shaped Cartier fake watches paypal. Comparing with Tonneau, its wider case had allowed for added complications from Monopusher Chronograph (1928) to Perpetual Calendar (2001) in its various interpretations.

This is the most spectacular piece in this current collection. The strike tones are even, a tad soft as this is a rather small timepiece encased in a solid gold case. But the beauty of the tortue case is endearing indeed. We carried a review of the classic time only Tortue here.

Tortue watch, large model, hand-wound mechanical movement, yellow gold, leather (2003)

Movement: 9401 MC

Characteristic: Manual winding

Power reserve: 42 hours

Frequency: 21,600 alt./hour

Number of jewels: 34

Collection Privée Cartier Paris (CPCP): Tonneau Dual Time Zone

The first Tonneau watch was born in 1906, which helped to challenge the tradition of round pocket Swiss made Cartier replica watches back in the days. Aimed to fit well on the wrist, the case was designed to curve slightly with the dial shaped in between a rectangle and an oval. The “vis armurier” tube screws adorning the lugs was a strong point of design to further enhance its avant-garde aesthetic in the early 1900s. Paired with a leather strap, its true beauty was underlined with the juxtaposition of precious and natural materials.

Tonneau watch, extra-large model, hand-wound mechanical movement, pink gold, leather (2005)

Movement: 9770 MC

Characteristic: Manual winding

Dimensions: 15.33mm by 2.9mm

Power reserve: 38 hours

Frequency: 21,600 alt./hour

Number of jewels: 18

Pasha High Complication Collection: Pasha de Cartier Golf

In 1985, the Maison introduced top quality Pasha de Cartier fake watches, a rounded case with a strong volume. Its name paid tribute to Pasha El Glaoui of Marrakesh, a loyal client of the Maison in the 1930s and watch collector. Apart from bearing the unique Cartier codes as seen in the square minute track in the centre of the dial and diamond hands, other new elements were introduced from rotating solid gold bezel to Arabic numerals.

Building on the success of its early years, the High Complication Collection saw new creations throughout the following decades. In 1987, the Maison offered Pasha de Cartier with minute repeater, moon phase and perpetual calendar. In 2020, the world saw the relaunch of Pasha de Cartier as an in-range offering.

Pasha de Cartier golf watch, 38 mm, manufacture mechanical movement with automatic winding, yellow gold, leather (1993)

Movement: 889 Jaeger

Characteristic: Automatic winding

Dimensions: 26mm by 4.1mm

Power reserve: 40 hours

Frequency: 19,800 alt./hour

Number of jewels: 34

Availability

The collection is available at the flagship Cartier boutique at ION Orchard opens from 10am to 9.30pm daily, subject to prior sale.